Book Review

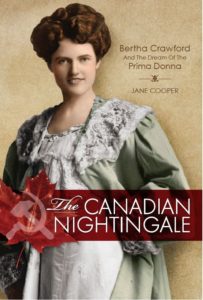

Jane Cooper.The Canadian Nightingale: Bertha Crawford and the Dream of the Prima Donna. Victoria, BC: Friesen Press, 2017. 334 pp., ill.

ISBN 978-1-5255-1740-2 (hardcover, $26.49) / 978-1-5255-1741-9 (paperback, $15.49) / 978-1-5255-1742-6 (eBook, $9.99). All prices are quoted from the Friesen Press website as of 14 November 2018. The book is also available from Indigo and Amazon. The author’s website about the book, including a video trailer for it, is here, and there is an article about Cooper and the book on Ottawa’s artsfile website here.

ISBN 978-1-5255-1740-2 (hardcover, $26.49) / 978-1-5255-1741-9 (paperback, $15.49) / 978-1-5255-1742-6 (eBook, $9.99). All prices are quoted from the Friesen Press website as of 14 November 2018. The book is also available from Indigo and Amazon. The author’s website about the book, including a video trailer for it, is here, and there is an article about Cooper and the book on Ottawa’s artsfile website here.

Jane Cooper was intrigued by a passing reference in a letter written by her great-aunt in 1924 about Berta Crawford, an English opera singer in Warsaw. She googled the singer’s name and learned that she was actually Canadian, not English. Her curiosity piqued, Cooper embarked upon what turned out to be a six-year research project that has resulted in this meticulously detailed and gracefully written biography. Undaunted by a lack of interest in her book from traditional publishers, Cooper launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise money and then had the biography produced by Friesen Press, a self-publishing outfit based in Victoria, BC. The resulting book meets the very highest editorial and production standards and is a worthy addition to the not terribly extensive library of books about Canadian opera singers.

Bertha May Crawford was born in Elmvale, Ontario (ca. 135 km north of Toronto) in 1886, and died in Toronto in 1937 at the age of fifty. The limited horizons those bare facts suggest – a life lived within the confines of a small area of southern Ontario – could not be further from the truth. After lessons with Edward Schuch in Toronto, Crawford was trained in London and Milan. Her career as a professional singer began in Italy but blossomed in Poland, and subsequent travels took her across the Russian empire, from Finland to Vladivostok. In Italy she had changed her name to Berta de Giovanni as a secret nod to her father, whose name was John (Giovanni in Italian). But after leaving Italy for Eastern Europe she dropped the “de Giovanni” while keeping the Italianate spelling of her first name, so she was “Berta Crawford” in Europe but reverted to “Bertha Crawford” for concerts in North America. For most of her career she was based in Warsaw, where she was highly regarded for her appearances as a coloratura soprano in opera, in concert, and later on the radio. Her signature roles were Gilda in Rigoletto, Rosina in The Barber of Seville, and Violetta in La traviata.

Crawford enjoyed a lengthy professional and personal relationship with Zofia Alexandra de Słubicka (née Kosińska), a wealthy and widowed Polish aristocrat whom she met in London. The two were inseparable friends by the end of 1912, and remained so for the next eighteen years. They lived together in Warsaw – perhaps, Cooper speculates, in a Boston marriage – and experienced the First World War, the Russian Revolution, and the creation of an independent Poland together, only to have a bitter falling out for unknown reasons in the early 1930s. After the break with her patroness and friend, Crawford returned to Toronto but died just three years later. Despite repeated attempts throughout her career, Crawford was unable to translate her successes in Poland and Russia into an international opera career. Aside from one appearance in a semi-professional production of Rigoletto in Washington, DC, she never sang in an opera production in North America. She did sing with orchestras and in solo recitals in Canada, and to a limited extent in the USA, but the “dream of the prima donna” eluded her on this side of the Atlantic Ocean.

The Great Depression, followed by the break with Zofia, left Crawford all but destitute. At the time of her sudden death from pneumonia in Toronto her career was effectively over and she was living on the edge of poverty. Her life was memorialized in numerous obituaries, but after her death Crawford quickly faded from memory. There were no recordings to preserve her voice for posterity, and no pupils to keep the memory of her career alive. The entry on Crawford in the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada reduced her life story to a mere four sentences. If Cooper’s curiosity had not been aroused, Crawford would remain all but unknown, the details of her life forgotten. But now Cooper has done a remarkable job of constructing a detailed narrative of Crawford’s life and career from countless bits and pieces of information that she unearthed in Canada, Poland, Russia, and online. In addition to this excellent biography, she has also contributed a fine Wikipedia entry on the singer.

Cooper presents two biographies within the covers of this one book. A factual biography unfolds chronologically in the course of the book’s fifteen chapters. There is a certain amount of conjecture, but it is always presented as such – the evidence of what happened is given first, followed by a number of possible interpretations, often presented as questions. Each chapter is followed by what Cooper labels an “entr’acte,” and these taken together comprise a second biography – or rather, a charming biographical novel. The entr’acte chapters consist of vignettes that illustrate important events in Crawford’s life. Each one was inspired by an actual historical artifact – a newspaper clipping, a photograph, and so on – but Cooper uses these concrete objects as springboards for her invention, presenting imagined conversations and richly detailed descriptions to provide a more rounded, if somewhat speculative, character portrait. In the wrong hands, this approach could have fallen flat, but happily Cooper is just as adept at historical fiction as she is at biography. The entr’acte chapters are entirely engaging and, to this ear at least, strike just the right tone. They capture the manners, customs, and conversational idioms of a bygone era without being at all contrived or awkward.

The extensive research that Cooper undertook is detailed in the acknowledgements, notes, archival sources, and bibliographical materials listed at the end of the book. She got in touch with Crawford’s living relatives, including a nephew, since deceased, who recalled having met Bertha, and others who had photos and clippings to share. Research trips to Poland and Russia resulted in many helpful contacts and unearthed further archival sources, and the Ancestry website proved useful in detailing not only Crawford’s family lineage but also her transatlantic crossings, thanks to that source’s extensive passenger records. Each phase of Crawford’s life and career, from her church choir positions in Toronto to her Polish radio performances, is presented in compelling and impressive detail. After a twenty-five year career as a policy analyst in Ottawa, Cooper has found a new calling as a Canadian music researcher. I look forward with keen anticipation to her next project, whatever it may be.