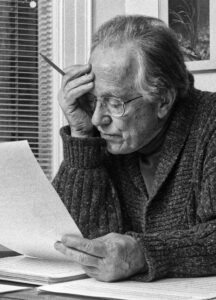

John Beckwith (1927–2022)

With the death of John Beckwith after a brief illness on December 5, 2022, at the age of 95, Canadian music has lost one of its most brilliant and constant champions. Born in Victoria, BC in 1927, Beckwith enjoyed a multi-faceted professional career that spanned eight decades; his vital contributions as a composer, educator, administrator, broadcaster, critic, writer, editor, and performer decisively shaped the musical life of this country during his lifetime. His many and varied achievements represent several careers worth of labour. He wrote over 160 articles, a similar number of original compositions, and many folksong arrangements. He continued to add to this vast output industriously to the end of his life: new compositions appeared regularly up until 2018, and his seventeenth book, Music Annals, was published earlier this year.

“The surname Beckwith is Anglo-Saxon, and it means ‘beechwood.’ My father’s branch of the family traces back to the emigration of Samuel Beckwith from his birthplace, Pontefract in Yorkshire, to the area near New London, Connecticut, in 1638.” So begins Beckwith’s engaging memoir, Unheard of (2012), which offers a frank and honest account of his life in rich detail. Beckwith was proud of the longstanding presence on this continent of his paternal ancestors, and it gave him a deep sense of rootedness. One of Samuel’s descendants moved to Nova Scotia in 1760, beginning the Canadian lineage of the family. A move across the continent in the 1880s took Beckwith’s grandfather to Victoria, where Beckwith’s father, the lawyer Harold Arthur Beckwith (1889–1958), was born. On the maternal line, the immigration from England dated from the late nineteenth century. Beckwith’s mother, Margaret Alice Dunn (1898–1990) was also born in Victoria and was a teacher before her marriage and again after her husband’s death. Both parents were enthusiastic amateur musicians and offered support and encouragement when John, the middle-born of their three children, showed an early talent in that direction.

Beckwith began piano lessons at age six and benefitted from the instruction of two very fine teachers in Victoria: first Ogreta McNeill (later a well-known music librarian in Toronto), and then Gwendoline Harper, with whom he studied for ten years. From Harper he learned not just a wide range of piano repertoire, but also theory, analysis, and general musicianship skills. From the age of eight onwards he appeared in public recitals and played in music competitions, often winning top prize, and sang in local choirs. He also attended live concerts regularly (a lifelong habit) and heard a wide range of music on the radio, including the standard symphonic and operatic repertoire and a healthy dose of modern music, which was to become his main interest. Beckwith thrived as a student at Oak Bay High during the war years, earning a citation for his involvement in journalism, drama, and music.

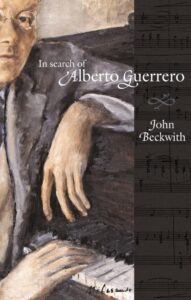

In 1945 Beckwith did his piano exam for the Associate diploma from the Toronto (soon to become Royal) Conservatory of Music. His examiner was the Chilean-born pianist Alberto Guerrero, who recommended the young pianist for a scholarship to study in Toronto. Guerrero was to be a formative influence; the young Glenn Gould was a fellow student at the time. During Beckwith’s concurrent studies at the University of Toronto Faculty of Music, his professors were Healey Willan, Leo Smith, and Ernest MacMillan. Fellow music students included the singers Lois Marshall and Mary Morrison, the composers Harry Freedman, Oskar Morawetz, Godfrey Ridout, and Harry Somers, and the future music librarian and Canadian music historian Helmut Kallmann. Through his involvement with drama productions, Beckwith met the writer James Reaney, who became a close friend and collaborator. After completing his BMus degree in 1947, Beckwith continued his studies for another year as a non-degree student, supplementing his scholarship money with a stint as the arts editor for the student newspaper The Varsity.

Beckwith began working as the publicity officer for the Royal Conservatory of Music in the fall of 1948, while continuing his piano studies with Guerrero. His public lecture-recital of Bach’s Goldberg Variations in 1950, the bicentennial of Bach’s death, met with high praise. By then, however, his interests were turning increasingly towards composition as the main outlet for his musical energies. In the fall of 1950, he married the teacher, pianist, and aspiring actor and director Pamela Terry, whom he had known since they were both teenagers in Victoria. The couple immediately set out for Paris, where Beckwith studied with the legendary Nadia Boulanger. He admired his famous teacher but kept his growing interest in the music of the post-war avant-garde to himself, as Boulanger had no sympathy for this repertoire.

Returning to Canada in the fall of 1952, Beckwith began putting together a varied career in music which included work as a critic, teacher, accompanist, and broadcaster/script writer for the CBC. As he once stated in a CBC interview, he could not recall any time since he was twelve that he did not have “at least three full-time jobs.” His CBC radio series Music in Our Time and The World of Music introduced listeners to modern compositions of the 1950s and 1960s, including electronic music and the work of John Cage.

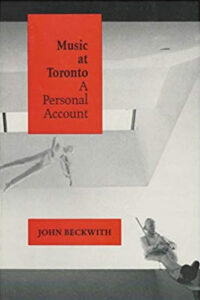

A major development in his career was a full-time appointment to the University of Toronto Faculty of Music in 1955, after three years of contract teaching there. He remained a full-time faculty member until 1990, served as the Dean of the Faculty of Music from 1970 to 1977 and as the inaugural Director of the Institute for Canadian Music from 1985 to 1991. His teaching duties were varied and included courses in theory, musicianship, music history, and composition; in 1966 he introduced the first course there on music in North America. His many pupils over the years include a who’s who of those active in the fields of composition and Canadian music studies. In retirement he wrote a fine short history of the Faculty for its 75th anniversary titled Music at Toronto: A Personal Account (1995).

A major development in his career was a full-time appointment to the University of Toronto Faculty of Music in 1955, after three years of contract teaching there. He remained a full-time faculty member until 1990, served as the Dean of the Faculty of Music from 1970 to 1977 and as the inaugural Director of the Institute for Canadian Music from 1985 to 1991. His teaching duties were varied and included courses in theory, musicianship, music history, and composition; in 1966 he introduced the first course there on music in North America. His many pupils over the years include a who’s who of those active in the fields of composition and Canadian music studies. In retirement he wrote a fine short history of the Faculty for its 75th anniversary titled Music at Toronto: A Personal Account (1995).

As a scholar-composer, Beckwith devoted equal energies to both academic publications and creative work. He contributed to every major Canadian music reference work as an editor or writer, or both, including Canadian Music Journal (1956–62), the monograph series Canadian Composers (1975–86), the biographical dictionary Contemporary Canadian Composers (1975), two editions of the Encyclopedia of Music in Canada (1981, 1992), and the 25-volume Canadian Musical Heritage anthology (1982–2003). Most of these projects were bilingual and benefitted from Beckwith’s excellent French-language skills and keen interest in the music of Quebec.

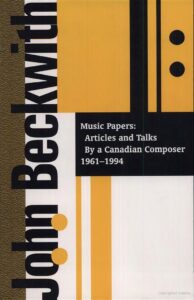

As a critic and commentator on radio and in the local newspapers, Beckwith liked to play the role of provocateur. His views could be forceful and sharp, but they were always insightful and well informed, and inevitably were offered with a view to setting the record straight. You always knew where he stood on matters, and why, and the strength of his opinions reflected the importance with which he viewed the issue at hand. The subject matter of his occasional pieces ranged widely, from Broadway to Boulez and beyond. He was an inveterate reader of the Globe and Mail and often penned letters to the editor when a review or article incensed him; many were published and many more were not. Two anthologies of his writings were published, Music Papers (1997) and Music Annals (2022). A particular labour of love was his study of his teacher Alberto Guererro, which entailed a research trip to Chile in 2003. In Search of Alberto Guerrero was published in English in 2006 and in Spanish translation in 2021. He co-edited a collection of essays about the composer John Weinzweig, another influential teacher and mentor, with his friend and former pupil Brian Cherney; it appeared in 2011.

While he had begun composing as a child in Victoria, it was not until after he had completed his BMus degree that setting notes to paper became a major preoccupation and indeed his main ambition. His creative and scholarly work fed into each other, quite literally in the case of the Concerto Fantasy for piano and orchestra, which was written under the supervision of Weinzweig and earned Beckwith the MMus degree from the University of Toronto in 1961. Beckwith’s compositions reflect many of his interests: Canadian literature and history; the country’s composed and traditional musical heritage; contemporary poetry, both Canadian and international; and the shifting currents of contemporary music. It is a rich tapestry, woven from varied strands of the Canadian experience, and stamped throughout with his personal style, which is by turns lively and introspective, serious and witty, demanding and accessible.

The catalogue of Beckwith’s compositions includes works in many instrumental and vocal/choral genres as well as opera. He proceeded largely by instinct rather than following a preordained method, but at the same time his compositions were carefully planned and executed according to rigorous organizational schemes, a unique one for each new work. Although some of these works were heard only once and then forgotten, many others have been recorded and there have been some notable revivals. His fine detective opera Crazy to Kill, for example, was given a splendid premiere at the Guelph Spring Festival in 1989 and was successfully remounted in a production by Toronto Masque Theatre in Toronto in 2011. Some works enjoy repertoire status, such as his 15-minute monodrama Stacey (1997) to words from Margaret Laurence’s novel The Fire-Dwellers. On numerous occasions, his music has been the sole focus of successful concerts, such as those given by Toronto’s New Music Concerts in 1996, 2003, and 2017. Scholarly interest in his compositions remains high, as witnessed by two recent doctoral theses at University of Toronto, one by Katy Clark on his four operatic collaborations with James Reaney, and another by Bradley Christensen on his prodigious song catalogue. The songs were performed by multiple singers and pianists in three 90-minute online recitals curated by Larry Beckwith for Confluence Concerts to celebrate the composer’s 94th birthday in 2021. It seems most likely that both Beckwith’s creative work as a composer and his scholarly legacy as a writer will endure for a very long time.

The public-facing activities of Beckwith were accompanied by a great deal of behind-the-scenes work as well. He helped to organize and/or served on the boards of the Canadian Music Centre, Ten Centuries Concerts, Canadian Opera Company, Canadian League of Composers, International Conference of Composers (Stratford, 1960), Encyclopedia of Music in Canada, Canadian Musical Heritage Society, Sir Ernest MacMillan Memorial Foundation, and the performing rights society BMI Canada, a forerunner of SOCAN. With increasing hearing loss in the late 1990s, Beckwith resigned from most such volunteer positions, but was able to continue his many other professional and social activities. His vital contributions to Canadian music were recognized by his appointment as a Member of the Order of Canada in 1987, by five honorary doctorates, and by numerous other awards.

With his wife Pamela Terry, Beckwith had four children. The couple separated in 1975 and divorced in 1980; Terry died at age 80 in 2006. Beckwith’s life partner for the past 45 years, Kathleen McMorrow, is the former head of the University of Toronto Music Library. The two shared a passion for epic bicycle trips across Canada and in many other parts of the world, for Scottish country dancing, for attending concerts several times a week, and for entertaining in their lovely home in Toronto’s Annex neighborhood. Beckwith’s death leaves a gaping void in the heart of the musical life of Toronto and of Canada, but his legacy will be carried on by the John Beckwith Fund of the Canadian University Music Society and the John Beckwith Award from the Canadian Music Centre. Beckwith was pre-deceased by his sister Sheila and his son Symon Francis, and is survived by McMorrow, his sister Jean [who died less than two weeks later, on December 18, 2022], daughter Robin, sons Jonathan and Lawrence (Larry), daughter-in-law Teri Dunn, granddaughters Fawn, Alison and Juliet, great-grandchildren Tristan and Elliott, and many nieces and nephews.

Other Tributes

CBC website [posted 6 Dec. 2022]

Ludwig van Toronto, by Anya Wassenberg [posted 6 Dec. 2022]

Globe and Mail, by Robin Elliott [posted 16 Dec. 2022]

Opera Canada website, by Larry Beckwith [posted 17 Dec. 2022]

Canadian Art Song Project, by Lawrence Wiliford [posted 19 Dec. 2022]

John Beckwith (1927–2022): Excerpts from a Life in Music, a blog post by Rebecca Shaw

about the U of T Music Library Exhibition that she has prepared